My son’s favorite hero is Spider-Man.

Specifically, Spiderman: Peter Parker. Thanks to the magic of character actors and a very committed birthday party, he actually met him on his fifth birthday. But, I don’t think the appeal is his web slinging or the acrobatics. I think he really loves Spider-Man because he sees himself in Peter Parker.

Peter Parker isn’t the biggest or the strongest. Peter’s not the most athletic or charismatic kid in the room. He’s gentle, he’s smart, and he’s kind. And, so is my son. And the idea that someone like that could randomly be imbued with incredible powers is what draws my son into Spider-Man’s web (dad joke fully intended).

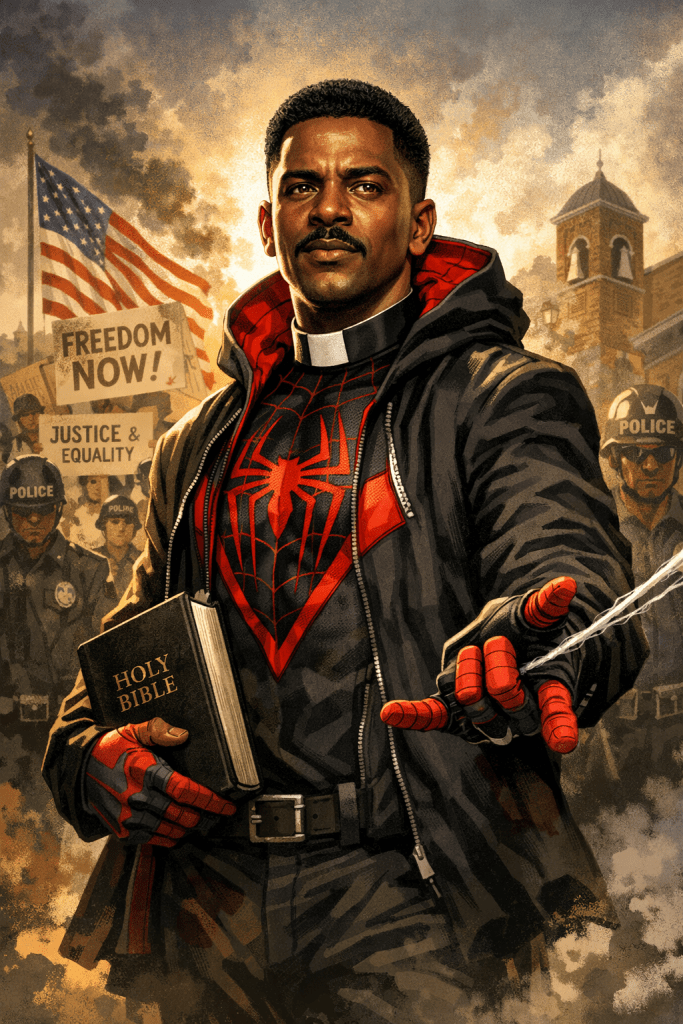

Personally, I’m much more drawn to Miles Morales.

I try not to judge my son’s preference… even though Miles is clearly the superior Spider-Man. I mean, c’mon! He wears Air Forces. He listens to hip-hop. I don’t even know what kind of music Peter Parker listens to. (He could be really into speed metal or ska, something weird, I bet.) But I digress. While my son values gentleness, curiosity, and kindness, I see myself in Miles’ experience of navigating multiple worlds at once. Code-switching between working-class home environments and elite educational spaces. Holding culture, language, and identity together while still trying to do the right thing and show up for the people you love.

Miles makes sense to me in a way that Peter Parker doesn’t, in a way that no other hero ever has.

What has been reveled in these father-son debates over who is the best hero is that we choose our heroes because of the values they represent and how they align with the values we treasure in ourselves.

Heroes tell us something important about values.

A Hometown Hero We Should All Know

Recently, I had the opportunity to talk about one of our hometown heroes here in Birmingham.

As part of the UAB High Reliability Organizing Program that our department at hosts alongside PressGaney, we take healthcare executives to the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute. Birmingham is known around the world as a birthplace of the Civil Rights Movement.

[I’ll pause here to say this: it has always bothered me that Birmingham’s reputation is often frozen in 1963. People struggle to separate the Birmingham of fire hoses and police dogs from the present-day reality, a city that is diverse, deeply engaged, and led by one of the most progressive mayors in the country. Birmingham is not stuck in its past, even as it remains deeply shaped by it.]

When civil rights are discussed nationally, the hero most people point to is Martin Luther King Jr., and rightly so as his leadership was instrumental to the movement. But here in Birmingham, we celebrate a different hero. A name that every American should know, because without his relentless push, not only might civil rights in this country have unfolded very differently, but we might not even know Dr. King as we do today.

His name was Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth.

For those who lived through the Civil Rights Movement, Shuttlesworth’s name sits alongside leaders like John Lewis, Ralph Abernathy, Bayard Rustin, Jesse Jackson, and Medgar Evers. But Shuttlesworth stood apart in one important way: he was often called the “Kingmaker.” He was the man who pushed (or sometimes dragged) the movement forward in Birmingham when others hesitated. Fred Shuttlesworth (seen in below photo behind MLK jr’s right shoulder) could be thought of as the righteous and formidable consciousness of the movement for civil rights.

When Shuttlesworth’s home was bombed on Christmas Morning in 1956 by the Ku Klux Klan, he emerged from the rubble unharmed. Witnesses said it looked like they had just seen Jesus walk on water. Many would have taken that as a sign to step back.

Shuttlesworth took it as a calling to press forward, undetered.

Later, determined to integrate Birmingham’s schools, he attempted to enroll his children—without the protection of the National Guard that surrounded the Little Rock Nine. When a mob surrounded his car, most parents would have driven away.

Fred Shuttlesworth got out of the car and opened the door for his children.

The mob attacked anyway. His wife was stabbed. Shuttlesworth was brutally beaten with brass knuckles. His daughter’s ankle was broken when the car door slammed shut as they escaped.

And still, he did not stop.

There are so many unbelieveable stories about Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth that deserve to be shared and lauded. He was an incredible man and we all owe him a debt of gratitude. Fred Shuttlesworth was a man on fire for justice. And, while I think he has no equal among us, Birmingham is a city shaped by people like him, deeply faithful, unafraid of confrontation when they believe righteousness is on their side, and aligned with Alabama’s motto: We Dare Defend Our Rights.

What Heroes Teach Us About Healthcare

Who we celebrate tells us what we value.

That’s true for comic books. It’s true for cities. And it’s true for healthcare organizations.

So I’ll ask the questions we don’t ask often enough:

Who are your hometown heroes?

What do they reveal about what your organization values?

How many of your heroes wear scrubs?

How many sit in hospital beds?

How many are patients whose courage, persistence, and lived experience quietly reshape care every day?

Healthcare doesn’t need more distant, untouchable superheroes. It needs heroes who know the block. Who understand the community. Who show up when it’s inconvenient and stay when it’s hard.

In other words, healthcare needs more friendly neighborhood heroes.

And maybe that’s where patient-led transformation really begins.

For more information about Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, I cannot recommend enough watching his PBS special for free here: https://www.pbs.org/show/shuttlesworth/

Resources:

https://civilrightstrail.com/experience/return-to-the-scenes-of-the-crime/